— Oscar Wilde.

Week 9 – Maker Movement

The Maker Movement has recently become a focal point of the classroom setting. The idea of using materials in our environment to solve problems has been used since the Stone Age (Martinez & Stager, 2014). However, the availability of educational technology in today’s society has seen this idea grow into the Maker Movement and a re-emergence of using new tools to enable hands-on, project-based learning.

Jean Piaget’s Constructivism and Seymour Papert’s Constructionism theories have helped demonstrate the importance of project-based learning and learning by doing in education (Piaget, 1976) (Papert & Harel, 1991). The Maker Movement acknowledges students as competent and lets them become the expert through exploring authentic tools and digital technologies. Through the design and construction of physical objects, students actively participate and engage while the informal and collaborative Maker Space environment helps encourage creativity, problem-solving and student-led learning (Bower et al. 2018).

Video from Vat19 Youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EWPKJF5enkk

Video Retrieved from LittleBits Electronics https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YUUsJSDa7PE

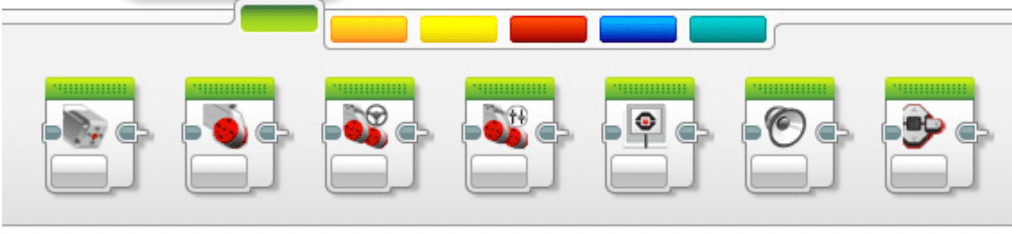

Makey Makey, LittleBits and Circuit Scribe are all technologies which allow students to be the focal point of learning and tasks them with constructing, organising and coding programs. These tools permit students to solve specific problems, explore learning outside their head and substitute traditional learning methods. Makey Makey allows users to connect everyday objects to computer programs, LittleBits uses block-based coding which snap together for immediate prototyping and feedback and Circuit Scribe allows immersive, hands-on experiences for learning how electricity and electronics work.

Video Retrieved from Circuit Scribe Youtube Page https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yxV8XBwy-tY

These technological tools create a Maker Space where students can personally explore and engage in their own project-based activities. They all focus on the idea that students’ knowledge is being formed from individual experiences and helped by the creative/collaborative learning environment. For these tools to allow positive student learning, it is crucial that teachers are provided with reliable technology, shared support, appropriate resources spaces and time to learn how they are going to implement through their own teaching practices. Learning in Maker Space must also be aligned to curriculum outcomes to be used effectively and should be used as tasks to replace regular learning not used in addition to.

References

Bower, M., Stevenson, M., Falloon, G., Forbes, A., & Hatzigianni, M. (2018). Makerspaces in primary school settings: advancing 21st century and STEM capabilities using 3D design and printing.

Martinez, S., & Stager, G. (2014). The maker movement: A learning revolution. Learning & Leading with Technology.

Papert, S., & Harel, I. (1991). Situating constructionism. Constructionism, 36(2), 1-11.

Piaget, J. (1976). Piaget’s theory. In Piaget and his school (pp. 11-23). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Week 8 – Games and Learning

Young children are often told that they can play their video games after they have completed their homework. Research is beginning to shift towards a world where students can play games as a part of their homework. While some researchers say there is not enough evidence for games in educational learning, opposing opinions consider that a good game is a space for problem solving to create deeper learning and the potential for more positive outcomes to be met than in tradition learning methods (Mayer, 2019).

While research for games-based learning is growing, the understanding of game-based pedagogy is still relatively unknown. For example, what role does the teacher and student have in game-based activities. Kangas, Koskinen & Krokfors (2017) have discovered that the teacher guides, supports and scaffolds learning in gameplay. Students are guided to answer questions and discuss what they may be learning through the activities and specific questions can focus student’s attention on concepts they are working through.

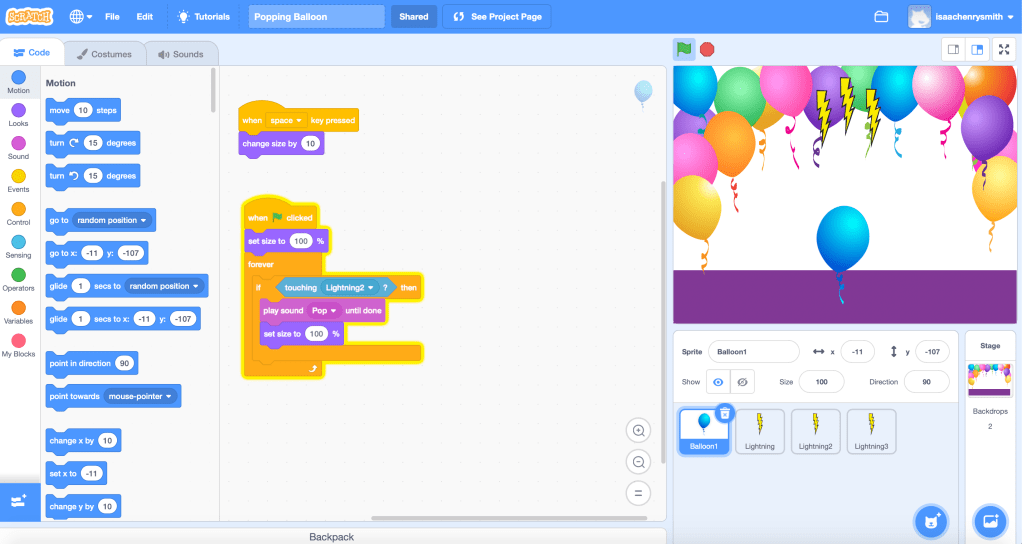

https://scratch.mit.edu/projects/393119317

Scratch is a great tool for game creation and helps tailor learning opportunities for individual student needs. While scratch is great for student learning, without explicit instruction, teachers may find the program difficult to follow and use productively. I have created a simple program for popping a balloon. However, without explicit instruction from the tutorial I would have gotten lost in the small details of scratch and where the icons and codes I needed were positioned.

Games are tools to help promote student-based learning. It is crucial that both teachers and students know their roles in order for games to be productive in a learning environment. While teachers are there to guide and assist, students need to use and develop their own skills to work through the activities. This also provides the opportunity for students to learn through failure. Games encourage resilience to students in a way that they may not see in normal learning environments.

References:

Kangas, M., Koskinen, A., & Krokfors, L. (2017). A qualitative literature review of educational games in the classroom: the teacher’s pedagogical activities. Teachers and Teaching, 23(4), 451-470.

Mayer, R. E. (2019). Computer games in education. Annual review of psychology, 70, 531-549.

Week 7 – Virtual Reality

Virtual Reality (VR) immerses users in an entirely simulated digital setting. Compare this to Augmented Reality (AR) which overlays virtual objects in real-world surroundings. This difference provides users with complete immersion and absorption rather than a combination of real and virtual worlds. While desktop VR has been around for decades, easily accessed Immersive Virtual Reality (IVR) is a reasonably recent experience. Desktop VR and IVR have varying degrees of user participation in virtual worlds (Southgate, 2018).

Research suggests that 3D Virtual Learning Environments can enhance spatial knowledge, facilitate experiential learning, connect virtual and real-life situations as well as motivate and engage learning (Dalgarno & Lee, 2010). Virtual Learning Environments (VLE) are also understood to develop creativity, increase student-led activities and focus on inquiry-based learning (De Freitas & Veletsiano, 2010).

VR in education sees a move from teacher-centred to child-centred classrooms and the application of CoSpaces is a great tool for students to be introduced to VR experiences (Al-Gindy et al. 2020). CoSpaces allows students to develop their own virtual world through access to a large library of graphics. Students also are provided with the availability to upload backgrounds, images, audio, video and begin to code on the built-in platform of CoBlocks.

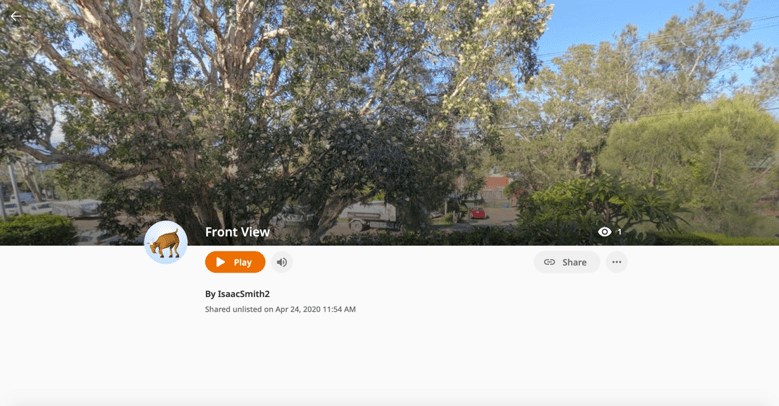

CoSpaces lets students take complete control over the development of their virtual world. Students can add a background from their own world to turn it into a virtual reality environment. However, CoSpaces requires explicit teacher instruction to be used appropriately and effectively. I developed a VR environment following explicit instructions from the EDUC3620 tutorial. Without instruction, I would have struggled to get everything uploaded correctly or understood how the platform-tools worked. This demonstrates that using CoSpaces in the classroom has both positives and negatives. Students need the correct skills to be productive and the learning tools to be beneficial.

References:

Al-Gindy, A., Felix, C., Ahmed, A., Matoug, A., & Alkhidir, M. (2020). Virtual Reality: Development of an Integrated Learning Environment for Education. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 10(3).

Dalgarno, B., & Lee, M. J. (2010). What are the learning affordances of 3‐D virtual environments? British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(1), 10-32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.01038.x

De Freitas, S., & Veletsianos, G. (2010). Crossing boundaries: Learning and teaching in virtual worlds. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(1), 3-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.01045.x

Southgate, E. (2018). Immersive virtual reality, children and school education: A literature review for teachers. DICE Report Series Number 6. Newcastle: DICE Research. Retrieved from http://dice.newcastle.edu.au/DRS_6_2018.pdf

Week 6 – Augmented Reality

Augmented Reality (AR) systems can be defined as the coexistence of real and virtual objects in the same space and used in actual time. AR has gained popularity within society but significantly education. The combination of real and virtual data provides users rich access to multimedia content that is both easily consumed but also contextually appropriate (Bower et al. 2014). The first uses of AR were seen through a tool for Air Force and Airline pilots during the 1990s (Murat Akçayır & Gokçe Akçayır, 2016). Akçayır & Akçayır (2016) discuss that the reason AR has become more popular in education environments is that it no longer requires expensive hardware or large and complex pieces of equipment. AR can be accessed through computers and mobile devices, and as a result, is being seen in all levels of schooling.

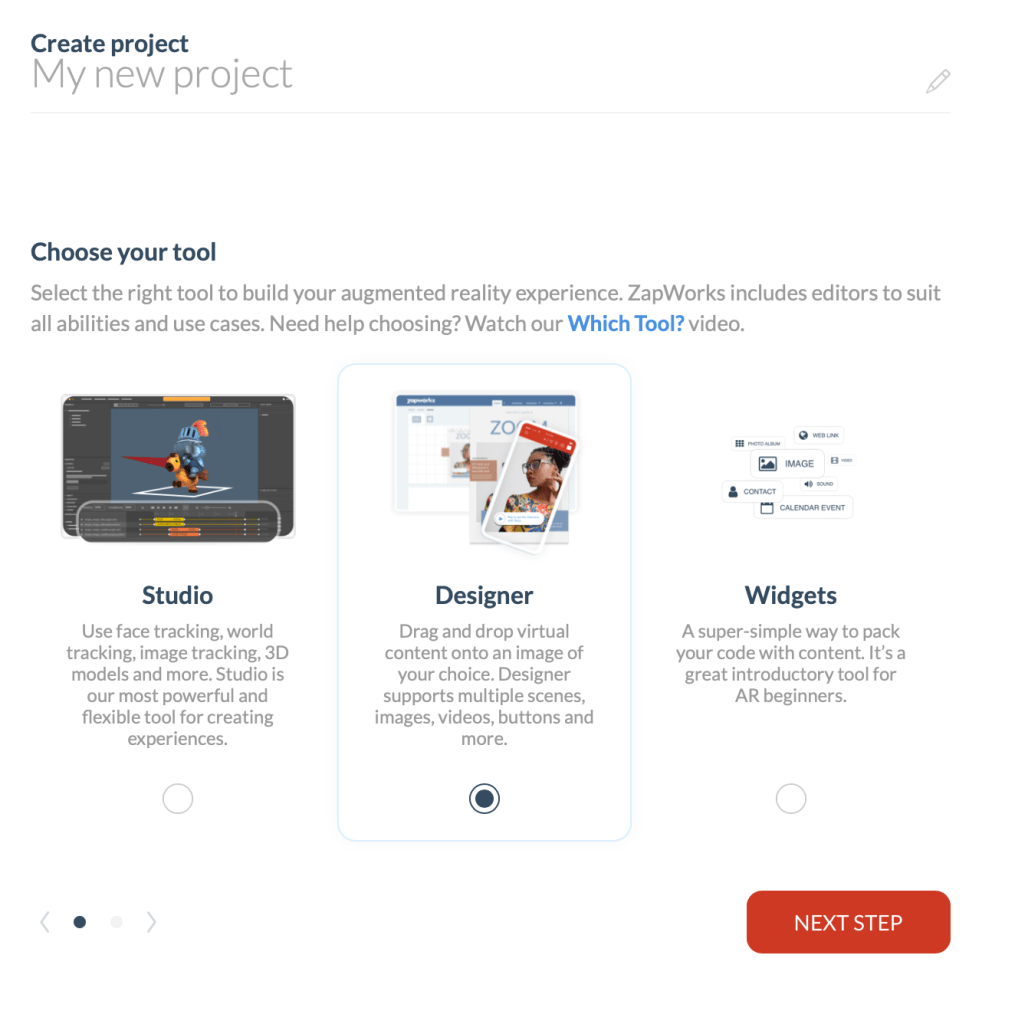

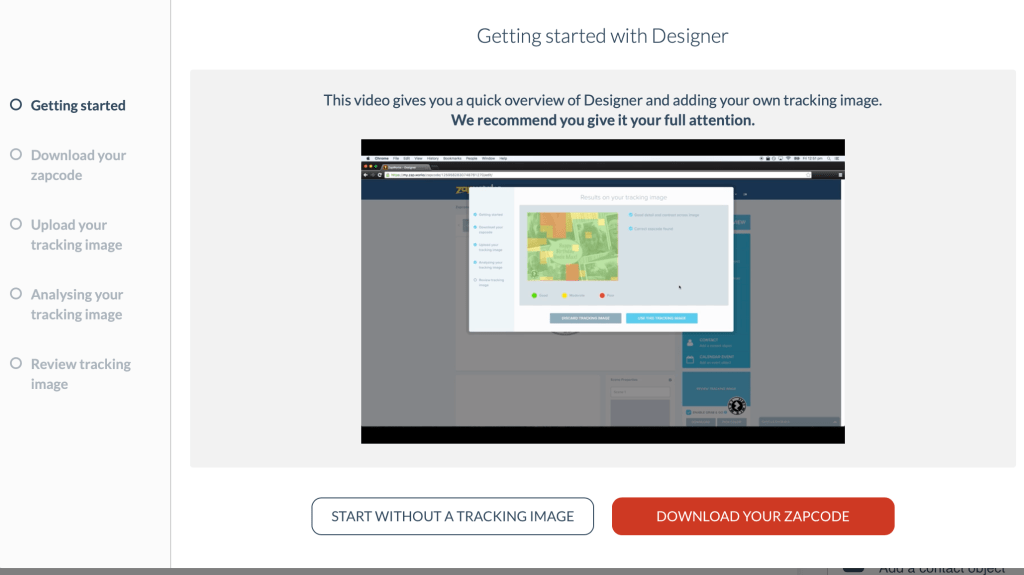

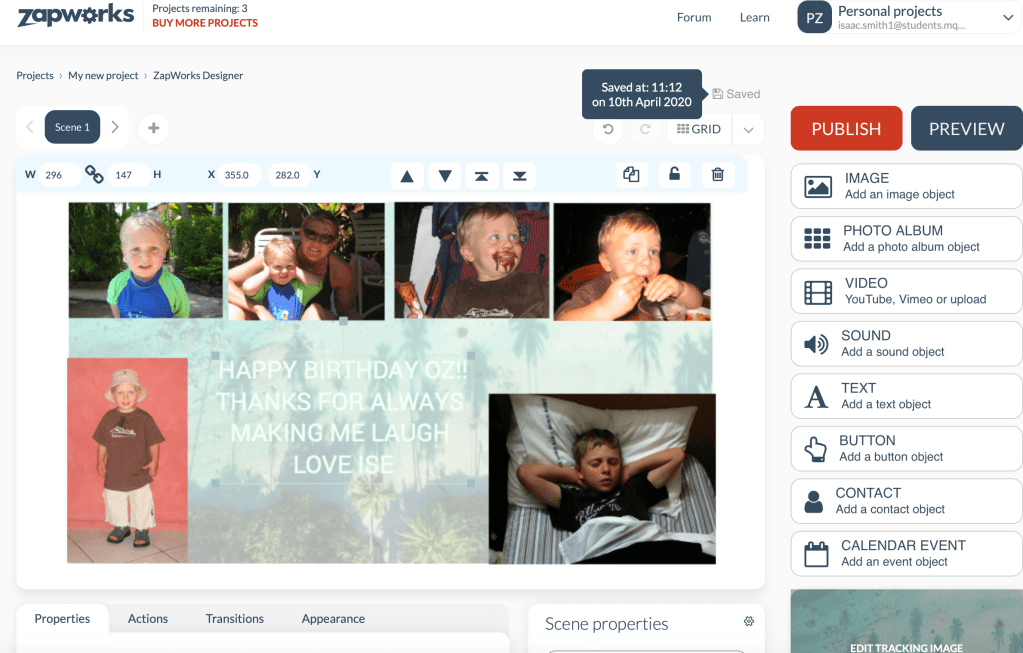

The use of Augmented Reality applications (AR apps) in an educational setting is becoming increasingly popular. The apps use a combination of software, sensors, and devices to present information and media concurrently with the surrounding reality (Bitter & Corral, 2014). Different apps can be used for different purposes e.g. SkyView can be used as a virtual education tool through the camera with the bottom left corner displaying relevant information to the object selected (Huang & Lin, 2017). Compare this to ZapWorks or Zappar, which has varying levels of difficulties from drag and drop development to completely customisable and scriptable 3D development (Seely, Creasy & Doll, 2019).

ZapWorks uses zapcodes to access content created by the user which is stored on the ZapWorks server. SkyView allows AR to be accessed, however, ZapWorks allows AR to be personally created, developed and opened, to build a more individual interaction with AR. For students, they are allowed to be creative and produce their own AR animation, while a simplistic launching and scanning procedure allows for fast and efficient experiences (Seely, Creasy & Doll, 2019).

To test out the simple drag-and-drop element of ZapWorks I made an Augmented birthday card for my younger brother. I found the ‘designer’ page a little confusing but once the zapcode was recognised, the images that appeared on the screen were an interesting way of viewing a card. In a classroom environment, AR allows students to instantly view their creations on screen. ZapWorks enables students to get creative, be engaged and feel empowered by developing their own experience.

References

Akçayır, M., & Akçayır, G. (2017). Advantages and challenges associated with augmented reality for education: A systematic review of the literature. Educational Research Review, 20, 1-11.

Bower, M., Howe, C., McCredie, N., Robinson, A., & Grover, D. (2014). Augmented Reality in education – Cases, places and potentials. Educational Media International, 51(1), 1-15

Bitter, G., & Corral, A. (2014). The pedagogical potential of augmented reality apps. International Journal of Engineering Science Invention, 3(10), 13-17.

Huang, Y. M., & Lin, P. H. (2017). Evaluating students’ learning achievement and flow experience with tablet PCs based on AR and tangible technology in u-learning. Library Hi Tech.

Seely, B. J., Creasy, A., & Doll, H. (2019). ZapWorks (Augmented Reality) Workshop.

Week 5 – Robotics

Robotics is used in education to teach problem-solving, programming, design, collaboration and creativity in all stages of learning. Robots as educational tools are used to both motivate learning and as concrete, hands-on material for teaching content (Miller & Nourbakhsh, 2016). Miller & Nourbakhsh (2016) believe robots have three roles to play in an educational setting: a robot as a programming project, a robot as a learning focus and a robot as a learning collaborator.

Alimisis (2012) believes that robotic technologies are not just tools, but possible methods of new ways of thinking for both teaching and student learning. Technologies allow students to actively participate in the learning process. While students can solely focus on hands-on learning, the teacher needs to organise, coordinate and facilitate the learning for the students. Without the teacher encouragement, collaboration and evaluation of robotics-based learning, students may not receive the full benefits of robotics (Alimisis, 2012).

The Ozobot robot is a small, lightweight toy that uses its senses to recognise different coloured lines. A positive of the Ozobot is that it can be used for a variety of age groups and year levels. The colour lines offer a nice tool for the younger years, while another way to control the robot is by coding on the Ozobot website http://ozoblockly.com/. Having a coding platform, blockly, means both teachers and students can access for free, on their own devices without needing to download software. The Ozobot main positives are its user-friendliness, price, wide age group suitability and prepared instruction (Fojtik, 2017).

Despite these positives, the Ozobot is a simple robot with only one senor and minimal functional movements. The motor is relatively weak, the coloured lines need to be perfect and the loading time of programs is time-consuming. There a numerous other educational robotics tools that have fewer limitations which include the BeeBot, Micro: bit, Dash and Dot, Lego Spike, mBo, Lego WeDo, and Lego EV3.

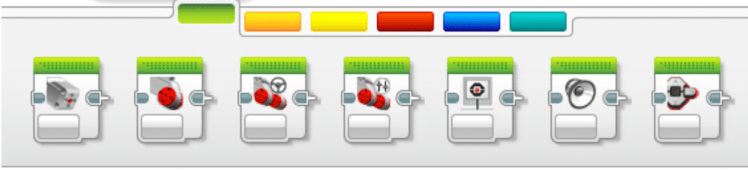

Lego WeDo robots are designed for younger age groups, however, they have the potential to target more difficult challenges, activities and year levels. WeDo uses a simple drag-and-drop block code. The blocks include cycle, wait command, motor motion, sensor inputs, sound replay, and value display. Compared to the Ozobot, the WeDo has motion and tilt sensors, constructible Lego components and an overall simpler interface (Kabatova & Pekarova, 2010). The Lego WeDo sets now come with a resource set to build more complex and interesting models (Mayerove & Veselovska, 2012).

While both the Ozobot and Lego WeDo robots are great tools to use in education settings, the Ozobot is limited in the activities that can be completed, compared to the Lego WeDo. The Lego WeDo is great for all ages, allows students to learn through action and lets the student learn through both imagination and instruction.

References:

Alimisis, Dimitris (2012). Robotics in Education & Education in Robotics: Shifting Focus from Technology to Pedagogy. Robotics in Education Conference, 2012.

Fojtik, R. (2017). The Ozobot and education of programming. New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences, 4(5).

Kabátová, M., & Pekárová, J. (2010). Learning how to teach robotics. In Constructionism 2010 conference.

Mayerové, K., & Veselovská, M. (2017). How to teach with LEGO WeDo at primary school. In Robotics in education (pp. 55-62). Springer, Cham.

Miller, D. P., & Nourbakhsh, I. (2016). Robotics for education. In Springer handbook of robotics (pp. 2115-2134). Springer, Cham.

Week 4 – Computational Thinking

Computational Thinking (CT) involves problem-solving, system designing and understanding certain human behaviour by using the ‘concepts’ of computer science not necessarily computer science itself (Wing, 2006). A common misconception of computational thinking is that it has to involve programming. CT focuses on developing thinking and problem-solving skills while within certain subjects beyond computer science (Voogt et al. 2015). An example of this could be in Stage 1 computational thinking, where students may be required to use basic algorithms (steps) to find a solution. This may be steps to brush their teeth or steps to pack their lunch, but not necessary programming or coding while still allowing students to be introduced to a computational way of thinking.

A computing education has been a focal point in schools for several years. However, recently the Department for Education (2013) has decided that focusing more closely on this will equip students with CT skills and creativity to understand and change the world they now live in. Despite this skill set being the leading focus of CT for students, the media continues to portray the idea that CT focuses solely on coding and in turn scares teachers but also students away from developing their skills.

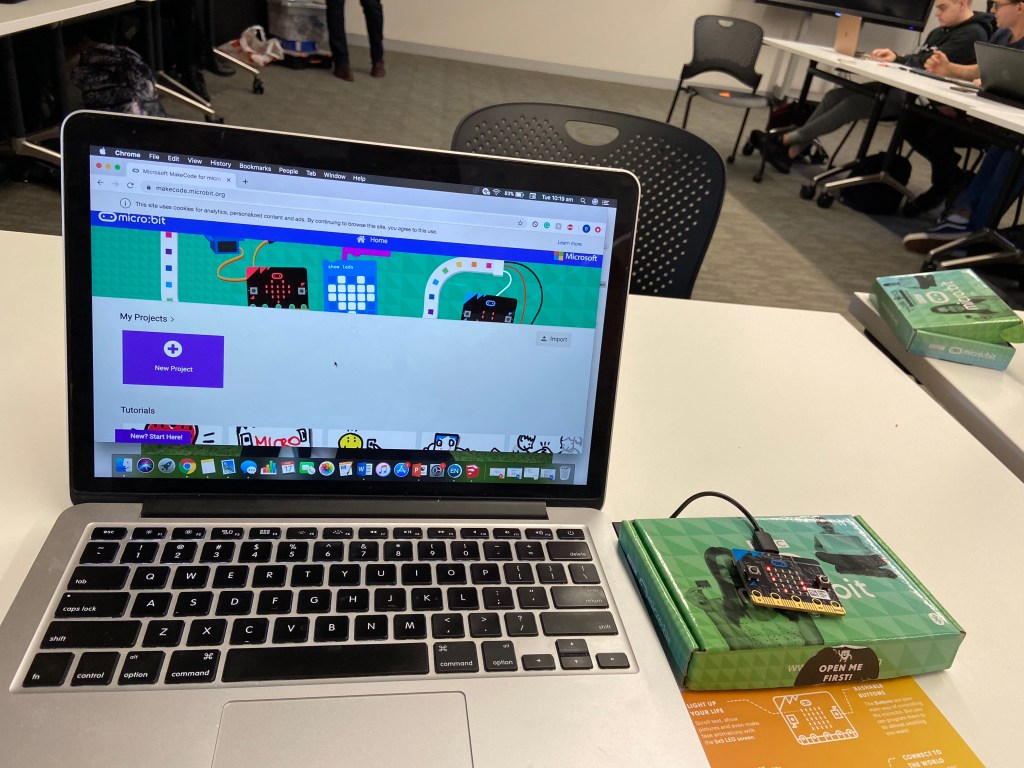

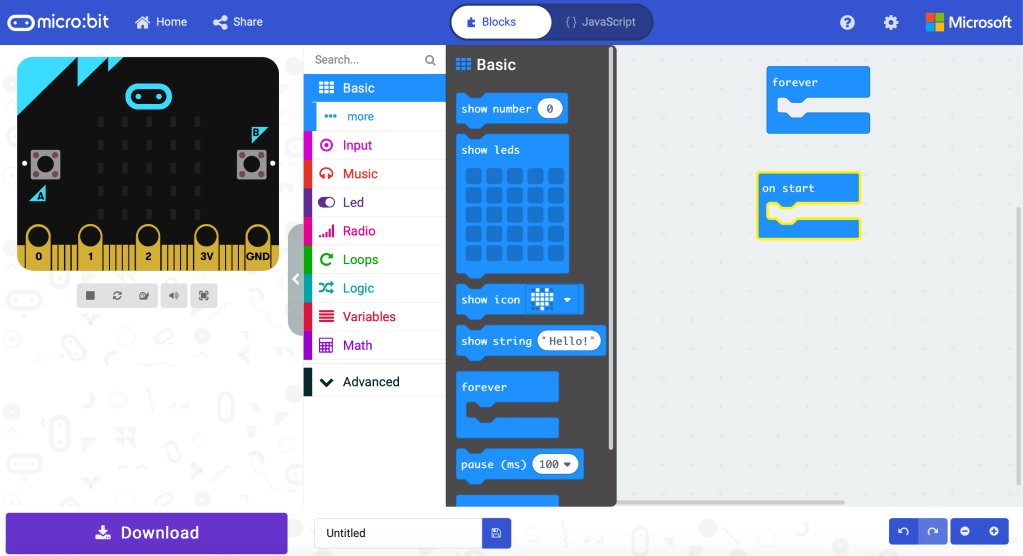

There are numerous ways for students to test their Computational Thinking skills in a classroom environment. Programming tools such as the Micro: bit or the Lego Mindstorms EV3 allow for tasks to be engaging, motivating and accessible by both teachers and students. The micro: bit is a pocket-sized computing device with the ability to be coded. The micro: bit was designed to be a part of a ‘Make it Digital’ initiative to inspire young people to use digital technologies to foster creativity in science, technology, and engineering. Through the use of programming, the micro: bit allows students to actively construct knowledge through hands-on physical engagement. This practical nature of CT sees benefits of higher motivation, collaboration, creativity and tangible concepts allowing real-life connections (Sentance et al. 2017).

Despite these positives, the micro: bit is a delicate and complex piece of technology that without explicit instruction is difficult to stay on task and therefore complete tasks. The website, coding platform and download function are complex and multifaceted and would be incredibly difficult to use when 35 students are having complications. Compare this to a Lego Mindstorms EV3, which is simple and intuitive to use (Molins-Ruani, Gonzalez-Sacristan, Garcia-Saura, 2018). The Lego Mindstorms coding platform uses simple block coding and an uncomplicated download system enabling students to easily send their codes to their robot.

While both the micro: bit and EV3 robot are great pieces of educational technology to use in a classroom environment, they each have advantages and disadvantages. Despite this, to make any activity successful and achieve outcomes, the quality of teaching plays a major role. This means that teachers have to feel comfortable and confident enough to use these products productively in their classroom to ensure students stay motivated, engaged and develop the appropriate CT skills.

References:

Curzon, P., Dorling, M., Ng, T., Selby, C., & Woollard, J. (2014). Developing computational thinking in the classroom: a framework.

Department for Education. (2013). The National Curriculum in England, Framework Document. (pp. 118)

Molins-Ruano, Gonzalez-Sacristan, & Garcia-Saura. (2018). Phogo: A low cost, free and “maker” revisit to Logo. Computers in Human Behaviour, 80, 428.

Sentance, S., Waite, J., Hodges, S., MacLeod, E., & Yeomans, L. (2017, March). ” Creating Cool Stuff” Pupils’ Experience of the BBC micro: bit. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGCSE technical symposium on computer science education (pp. 531-536).

Voogt, J., Fisser, P., Good, J., Mishra, P., & Yadav, A. (2015). Computational thinking in compulsory education: Towards an agenda for research and practice. Education and Information Technologies, 20(4), 715-728.

Wing, J. M. (2006). Computational thinking. Communications of the ACM, 49(3), 33-35.

Week 3 – 3D Printing

Active learning is defined by van Hout-Wolters, Simons & Volet (2000) as a form of learning which allows the learner to adapt the opportunities provided to take control of their own learning process. Technology also allows students to learn in different and amazing ways (Kwon, 2017). While technology is a great tool for independent work, using it in a classroom environment helps students with collaboration, problem solving and critical thinking skills.

Because technology is prevalent in our society, it is crucial students can experience technology while learning as they will be using it in their own careers. Students enjoy learning through the use of technology. Therefore, introducing various KLA’s to students through technology will increase excitement as they have a better understanding of the area of study (Kwon, 2017).

The use of 3D desktop printing, while still being relatively new, is quickly developing with an ever-growing potential. 3D printing supports visual learning through the creation of tangible representations while the process of 3D designing allows for students to visualise information, feedback and experimentation. This visual learning capacity isn’t made available when students are learning with pen and paper. This demonstrates that the use of 3D printing and design helps students better understand complex and more difficult ideas (Lacey, 2010).

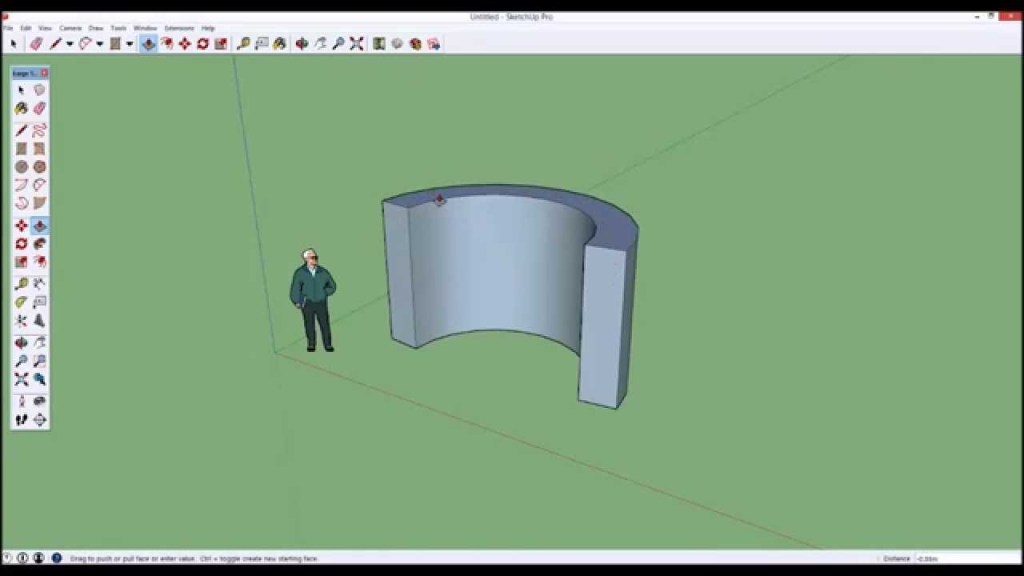

In a classroom setting, 3D printing can be done on Tinkercad, Google SketchUp or a variety of different free or paid design packages (Berman, 2012). Google SketchUp provides an interface which is very simple using tools from other software packages such as Microsoft paint and photoshop allowing new users the opportunity to explore the tools in a variety of settings (Singh, 2010).

While 3D printing is a great tool for engaging students and enabling visual and more complex learning, there are a few downsides. A 3D printer can cost at the lower end, around $10,000 (Berman, 2012). Most schools do not have the funding to be able to introduce this into school and therefore incorporated into daily lessons. 3D printing and design is also a time-consuming activity. While the software of SketchUp provides a simple interface, completing an entire lesson, without distractions in a classroom environment is a difficult goal for teachers. Despite these negatives, an introduction into 3D printing for students allows for students to visually engage in learning as well as the opportunity to move into more complex ideas.

References:

Berman, B. (2012). 3-D printing: The new industrial revolution. Business horizons, 55(2), 155-162.

Kwon, H. (2017). Effects of 3D Printing and Design Software on Students’ Overall Performance, Journal of STEM Education, 18(4), 37-42.

Lacey, G. (2010). 3D printing brings designs to life. Tech Directions, 70 (2), 17-19.

Singh, S. (2011). Beginning google sketchup for 3D printing. Apress.

van Hout-Wolters, B., Simons, R. J., & Volet, S. (2000). Active learning: Self-directed learning and independent work. In New learning (pp. 21-36). Springer, Dordrecht.

Task 1 – Learning Technology Critique

Creative teaching, irrespective of an inclusion of technology is a complicated and limitless area (Henriksen, Koehler and Mishra, 2016). In the 21st century, with the continual advancements of educational technology, combining creative teaching and effective uses of technology becomes an even more complicated problem. There are countless old and new educational technologies that are used in a classroom environment for a variety of KLAs and outcomes. Learning technologies are best when they are interactive, hands-on, collaborative and allow students to problem solve and use their own creativity in order to find a solution.

EV3 Lego Mindstorms were created as a collaboration between MIT and the Lego Group in 1988. They designed a basic intelligence brick that is able to be coded or programmed by a computer (Molins-Ruani, Gonzalez-Sacristan, Garcia-Saura, 2017). Molins-Ruani, Gonzalez-Sacristan, Garcia-Saura (2017) stated that the block-based language is simple and intuitive to use, and while this is somewhat true, without explicit instruction, teachers, but more importantly, students will find it very difficult to use on their own without extensive instruction. Programming and coding through the Mindstorms platform is a great educational tool in STEM classes but the opportunities with EV3s do not stop there.

As a Lego Mindstorms EV3 incursion facilitator, I can see the opportunity to focus on inquiry-based learning rather than explicit instruction. Inquiry based learning is often defined as the process of discovering new connecting relations, the ability to solve problems with a strong emphasis on active participation as well as placing the responsibility on the learners to uncover new knowledges (Pedaste et al. 2015). This will allow for students to use their creativity skills in collaboration with their peers. While this is achievable for me with a knowledge of the Mindstorms platform and the robot itself, teachers who have not seen then robots before may strongly disagree.

Once the robots are connected to their corresponding laptop and a brief run through of the Action Blocks, students are then free to complete the set task, working collaboratively with guess and check, trial and error and further problem-solving skills. This opportunity for student lead discoveries is why EV3s can be a great tool to enhance creativity.

The major limitations to EV3s as a learning technology in the classroom which need to be considered are the teacher training that may be required on both programming and robotics, as well as the high costs involved. Schools often do not have the funds to purchase EV3 robots and laptops for an entire class to use, and therefore make this learning technology difficult to justify.

References

Henriksen, D., Mishra, P., & Fisser, P. (2016). Infusing creativity and technology in 21st century education: A systemic view for change. Educational Technology & Society, 19(3), 27-37.

Molins-Ruano, Gonzalez-Sacristan, & Garcia-Saura. (2018). Phogo: A low cost, free and “maker” revisit to Logo. Computers in Human Behavior, 80, 428.

Pedaste, M., Mäeots, M., Siiman, L. A., De Jong, T., Van Riesen, S. A., Kamp, E. T., … & Tsourlidaki, E. (2015). Phases of inquiry-based learning: Definitions and the inquiry cycle. Educational research review, 14, 47-61.

Introduce Yourself (Example Post)

This is an example post, originally published as part of Blogging University. Enroll in one of our ten programs, and start your blog right.

You’re going to publish a post today. Don’t worry about how your blog looks. Don’t worry if you haven’t given it a name yet, or you’re feeling overwhelmed. Just click the “New Post” button, and tell us why you’re here.

Why do this?

- Because it gives new readers context. What are you about? Why should they read your blog?

- Because it will help you focus you own ideas about your blog and what you’d like to do with it.

The post can be short or long, a personal intro to your life or a bloggy mission statement, a manifesto for the future or a simple outline of your the types of things you hope to publish.

To help you get started, here are a few questions:

- Why are you blogging publicly, rather than keeping a personal journal?

- What topics do you think you’ll write about?

- Who would you love to connect with via your blog?

- If you blog successfully throughout the next year, what would you hope to have accomplished?

You’re not locked into any of this; one of the wonderful things about blogs is how they constantly evolve as we learn, grow, and interact with one another — but it’s good to know where and why you started, and articulating your goals may just give you a few other post ideas.

Can’t think how to get started? Just write the first thing that pops into your head. Anne Lamott, author of a book on writing we love, says that you need to give yourself permission to write a “crappy first draft”. Anne makes a great point — just start writing, and worry about editing it later.

When you’re ready to publish, give your post three to five tags that describe your blog’s focus — writing, photography, fiction, parenting, food, cars, movies, sports, whatever. These tags will help others who care about your topics find you in the Reader. Make sure one of the tags is “zerotohero,” so other new bloggers can find you, too.